Genobiography: Tristan Begg’s pioneering research uncovers clues to Beethoven’s health and family secrets

Tristan Begg, a PhD student in Biological Anthropology and member of Clare Hall, University of Cambridge, is the lead author of a ground-breaking study deciphering Ludwig van Beethoven’s genome from five genetically matching locks of the composer’s hair.

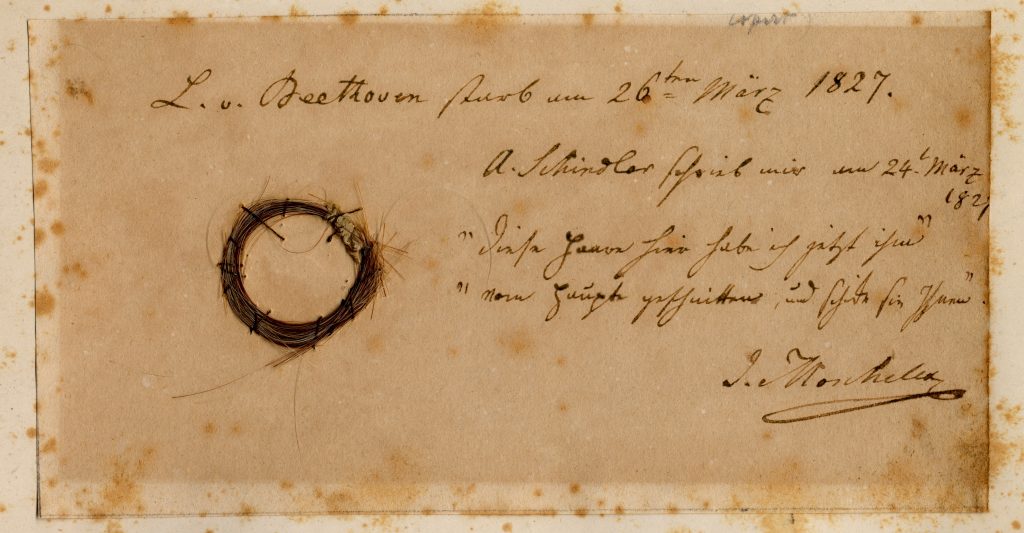

Courtesy Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San Jose State University.

Conducted by an international team of scientists, the study demonstrates that Beethoven was predisposed to liver disease and infected with Hepatitis B, which combined with alcohol consumption may have contributed to his death. Additionally, DNA from modern relatives points to an extramarital ‘event’ in Beethoven’s paternal line.

In 1802, Beethoven asked his doctor to describe his illness and to make this record public, yet without the benefit of genetic research, his health and cause of death have been debated ever since. Research published in Current Biology shows that DNA from five locks of hair – all dating from the last seven years of Beethoven’s life – originate from a single individual matching the composer’s documented ancestry. By combining genetic data with closely-examined provenance histories, researchers conclude these five locks are ‘almost certainly authentic’.

The study’s primary aim was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously included progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s, eventually leading to him being functionally deaf by 1818. The team also investigated possible genetic causes of Beethoven’s chronic gastrointestinal complaints, and a severe liver disease that culminated in his death in 1827.

Beginning in his Bonn years, the composer suffered from ‘wretched’ gastrointestinal problems, which continued and worsened in Vienna. In the summer of 1821, Beethoven had the first of at least two attacks of jaundice – a symptom of liver disease. Cirrhosis has long been viewed as the most likely cause of his death aged 56.

The team of scientists was unable to find a definitive cause for Beethoven’s deafness or gastrointestinal problems. However, they did discover a number of significant genetic risk factors for liver disease. They also uncovered evidence of an infection with Hepatitis B virus in the months before the composer’s final illness.

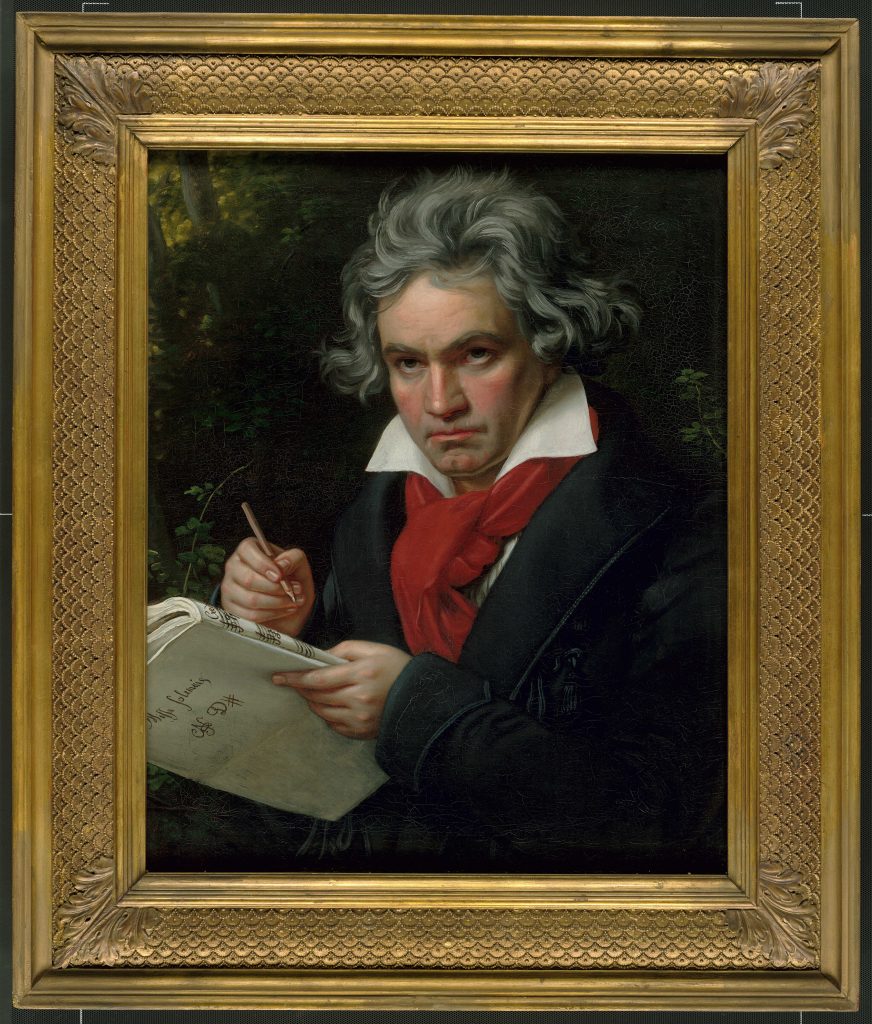

Courtesy Beethoven-Haus Bonn

Tristan comments:

‘We can surmise from Beethoven’s “conversation books”, which he used during the last decade of his life, that his alcohol consumption was very regular – although it is difficult to estimate the volumes being consumed. While most of his contemporaries claim his consumption was moderate by early nineteenth-century Viennese standards, there is not complete agreement among these sources, and this still likely amounted to quantities of alcohol known today to be harmful to the liver. If his alcohol consumption was sufficiently heavy over a long enough period of time, the interaction with his genetic risk factors presents one possible explanation for his cirrhosis.’

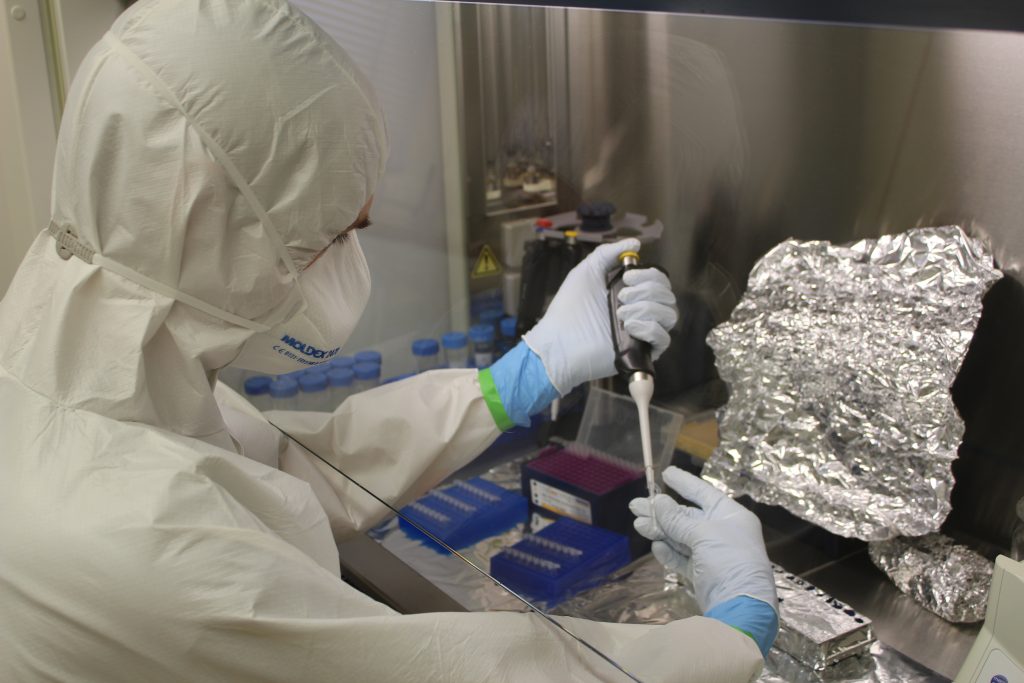

Working in close affiliation with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Tristan is a dual citizen of the United States and the United Kingdom, and grew up predominately in San Jose, California. His undergraduate background from UC Santa Cruz is in Physical Anthropology – focusing on skeletal remains and human evolution – and he transitioned to ancient DNA during his MSc at the University of Tuebingen. Tristan’s PhD work follows his previous research aiming to improve the material and economic efficiency of extracting genomic quantities of DNA from small quantities of ancient and historic hair. He hopes that combining these methodological improvements with the dramatic advances in medical genetics will enable historians and biographers to analyse the genomes of historical individuals from whom hair samples abound, and to address particular questions in historical biography that genetics is well suited to answer. He is terming his subdiscipline ‘Genobiography’.

The team additionally analysed the genetics of Beethoven’s living relatives in Belgium, but could not find matches among either of them. Some of them share a paternal ancestor with Beethoven in the late 1500s and early 1600s based on genealogical studies, but they did not match the Y-Chromosome found in the authentic hair samples. The team concluded that this was likely to be the result of at least one ‘extra-pair paternity event’ – a child resulting from an extramarital relationship – in Beethoven’s direct paternal line.

The study suggests that this event occurred in the direct paternal line between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in Kampenhout, Belgium in c.1572, and the conception of Ludwig van Beethoven seven generations later in 1770, in Bonn, Germany. Although a doubt had earlier been raised concerning the paternity of Beethoven’s father owing to the absence of a baptismal record, the researchers could not determine the generation during which this event took place.

Tristan adds:

‘We hope that by making Beethoven’s genome publicly available for researchers, and perhaps adding further authenticated locks to the initial chronological series, remaining questions about his health and genealogy can someday be answered.’

This research has been led by the University of Cambridge, the Beethoven Center San Jose and American Beethoven Society, KU Leuven, FamilyTreeDNA, the University Hospital Bonn and the University of Bonn, the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

On his time at Clare Hall to date, Tristan shares:

I want to express my profound gratitude to Clare Hall for always providing such a welcoming and stimulating environment during my time in Cambridge. Some of the bioinformatics research on the locks of hair, including the discovery of Beethoven’s major heritable liver disease risk factors using imputed genotypes from an early draft of Beethoven’s genome, in fact took place right in the Porters’ Lodge in Clare Hall. The College will forever hold an extremely precious place in my heart, and I want to thank all of the graduate students, Fellows, visiting scholars, staff, friends and finally my fiancée, Chuchen, who I met during our first matriculation lunch in Clare Hall, for having made my time in Cambridge so memorable.

Read the paper in full at https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(23)00181-1

About Clare Hall

Clare Hall is a college for advanced study at the University of Cambridge. Located close to the University Library, the College offers an intellectually stimulating, interdisciplinary setting for postgraduate students and scholars.