Dr Anthony Harris decodes rare manuscripts in Harvard University’s Houghton Library

Research Fellow Dr Anthony Harris is currently a visiting Fulbright Scholar in medieval studies at Harvard University, and has recently helped to decode several rare manuscripts in the Houghton Library as part of the exhibition “The Crusades Come to Cambridge.”

The exhibition explores the fascination among Americans of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the Crusades and the European Middle Ages generally. In 1899, members of the wealthy Coolidge family of Boston purchased, on behalf of Harvard, two-thirds of the library of Paul Édouard Didier Riant (1836–1888), one of the 19th century’s most well-known Crusades scholars. Riant’s library contained medieval and modern manuscripts, incunables, pamphlets, maps, and other materials related to the study of the Crusades and Latin East. Although the materials have been used only sparingly in the 125 years since their arrival, they offer enormous possibilities for researchers interested in medieval sources.

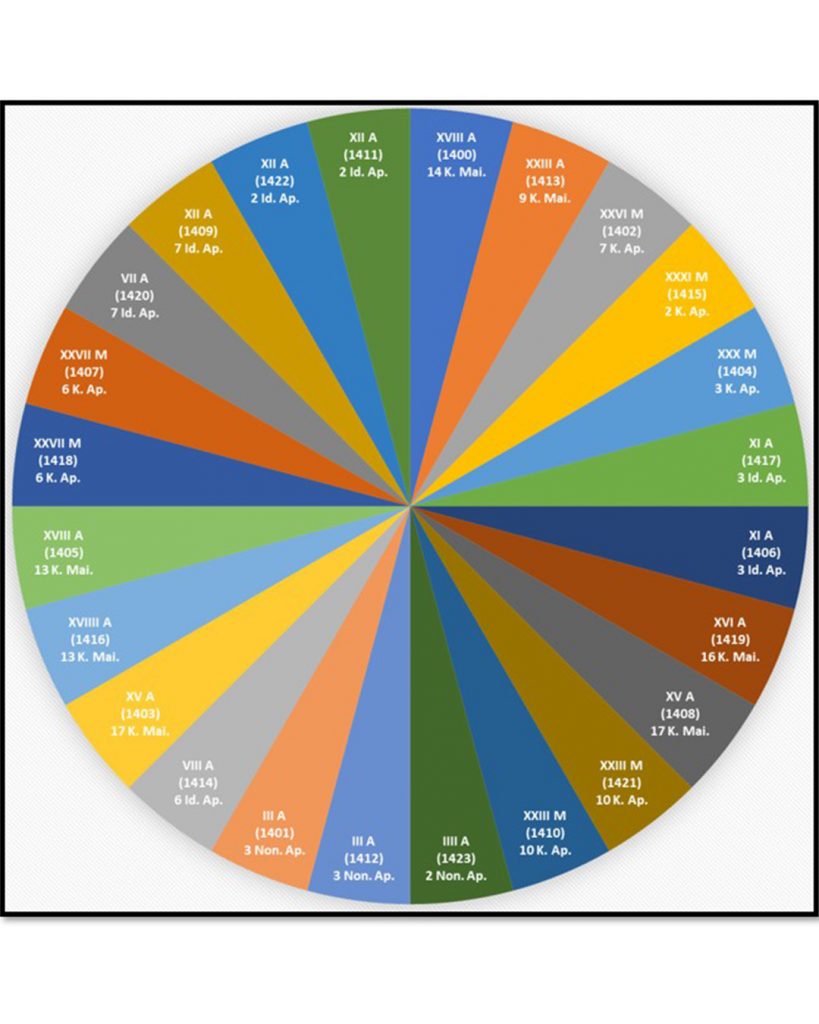

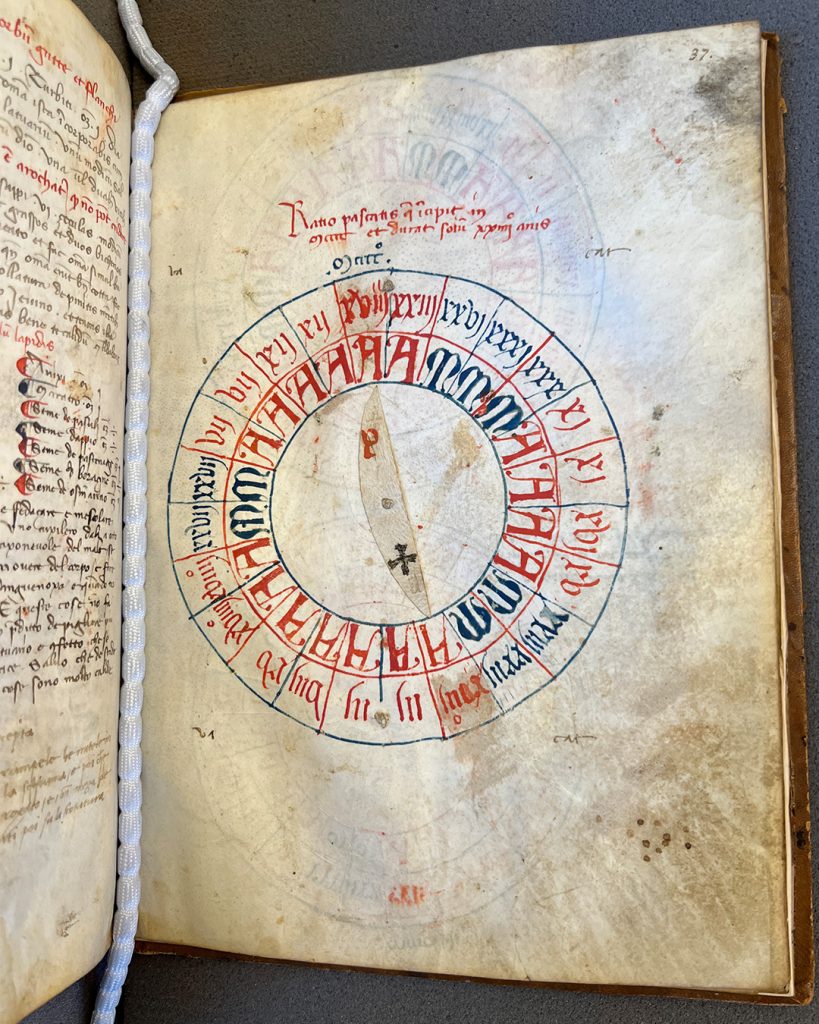

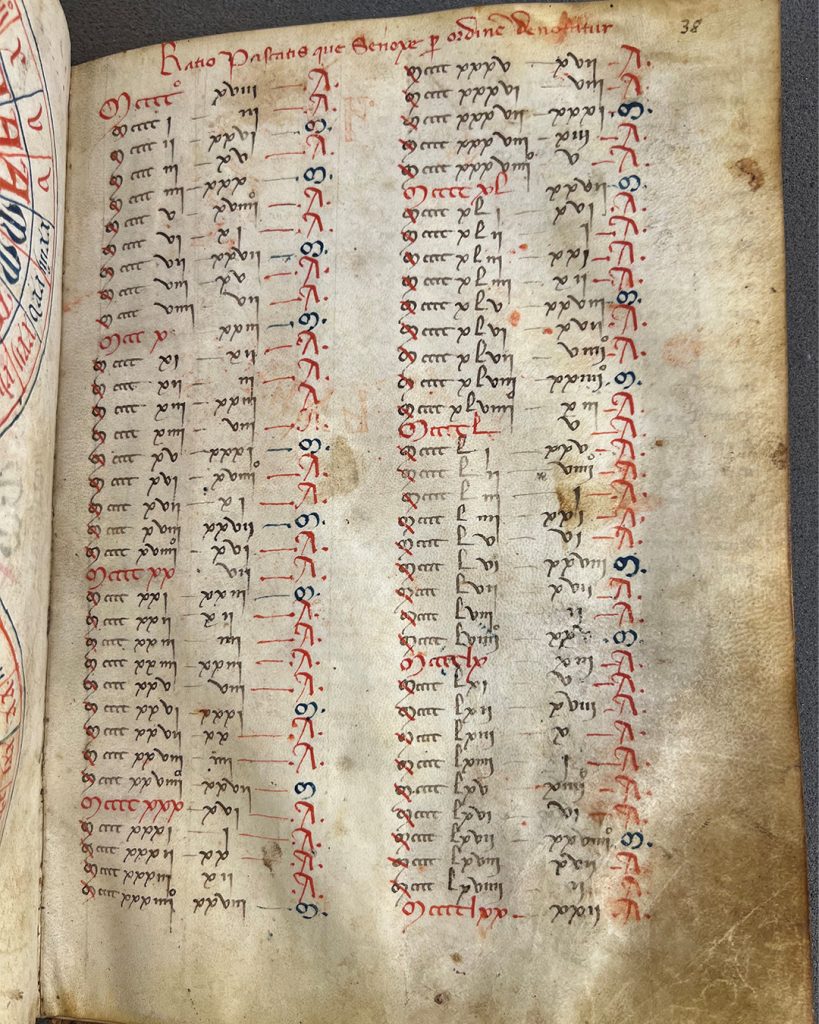

One featured manuscript, MS Riant 81, contains three large circular charts with rotating volvelles used to calculate the date when Easter occurs, which have posed some interpretive challenges. Dr Harris has examined these volvelles and revealed the following: ‘The volvelle on f. 37r is somewhat ingenious and could well be the work of a computus master. The scribe identifies it as ‘Ratio pascatis qui incipit in MCCCC (1400) et durat solum XXIIII (24) annis’ so we might expect it to be an Easter calculator for the 24-year cycle 1400–1423. This is confirmed when we see that the numbers on the outside of the volvelle refer to the number of the calendar day (from 1 = Kalends) of the 24 Easter dates in 1400–1423. These calendar days are found in either the ‘(M)arch’ (f. 2r) or ‘(A)pril’ (f. 2v) folios of the liturgical calendar in the same manuscript. Hence, Roman numeral XXX M refers to day 30 in March, or 3 Kal. Ap. (Sunday 30 March) for the year 1404. Similarly, continuing around the volvelle in a clockwise direction, we see IIII A (corrected by the scribe from XV) which refers to day 4 in April, or 2 Non. Ap. (Sunday 4 April) for the year 1423. Of course, in the period, any monastic computist would have known the correspondence between day numbers and Roman style dates without needing to refer to a calendar. Once the coding system described here is understood, then the use of the volvelle becomes readily apparent. For example, turning the ‘P’ end of the pointer to the 12-O’clock position (XVIII A) gives the Easter date for the year 1400 as April day 18 or 14 Kal. Mai (Sunday 18 April). Correspondingly, the ‘+’ end of the pointer (III A) now gives the Easter date for 1412 as April day 3 or 3 Non. Ap. (Sunday 3 April). In all cases the day of the week is implied, because Easter day can only fall on a Sunday. The construction of the volvelle is ingenious in that (reading clockwise from the midday position) odd numbered segments 1, 3, 5, 7 etc. correspond to years 1400, 1402, 1404, continuing by two each time and ranging from 1400 to 1422 (segment 23). By comparison, the even numbered segments, 2, 4, 6, 8 etc. run from 1413–1423 (segment 11) and then restart at 1401 (segment 13) and continue to 1411 (segment 24) incrementing by two each time. Hence, the volvelle is designed so that the top and bottom of the pointer always give dates that are 12-years apart, 1400–1412, 1413–1401, 1402–1414 etc.’

Pictured above: Calendars and prayers. Manuscript: Italy, 15th century. MS Riant 81. Gift of J. Randolph Coolidge and Archibald Cary Coolidge, 1899. Courtesy of Anthony Harris.